Ukraine-Russia War

Image Credit: Getty Images

The image depicts a military scene with a vehicle-mounted rocket launcher firing a missile, leaving a bright exhaust trail as it ascends. The vehicle, camouflaged and set against a rugged, barren landscape, underscores the harsh conditions of a conflict zone. A soldier in combat gear stands to the right, using a handheld radio, suggesting active military operations. This stark scene illustrates the destructive force of warfare and its severe environmental and human consequences.

Introduction

War and climate change are two interconnected crises shaping the world for centuries, pushing us towards a precarious future. This relationship can be traced back to ancient civilizations, where environmental degradation often led to social unrest and conflict. For instance, the collapse of the Akkadian Empire around 2100 BCE and the decline of the Maya civilization around 900 CE were influenced by environmental factors such as deforestation and drought. The Industrial Revolution further exacerbated this connection, leading to widespread deforestation and pollution, significantly contributing to climate change.

Modern conflicts over resources like oil, water, and land continue to highlight this interplay. Historical wars, including World War I and II, the Vietnam War, and the Gulf War, have caused extensive environmental damage, from deforestation and chemical contamination to severe air and water pollution. Recent conflicts, such as those in Iraq and Afghanistan, and ongoing wars like the Russia-Ukraine conflict continue to devastate ecosystems, agricultural lands, and water resources, exacerbating global warming.

This blog aims to illuminate the complex interplay between war, climate change, and environmental degradation, underscoring the urgent need for comprehensive strategies to address these interconnected challenges. By exploring the security implications of war-induced climate change and the risks of potential civilizational collapse, we emphasize the critical importance of proactive and sustainable solutions. Investigating how individuals and communities can contribute to mitigating these threats, fostering resilience, and working towards a more sustainable and secure future is essential.

The Green Battlefield: How War is Destroying Our Planet

Wars have long been recognized for their immediate human toll, but their environmental impacts are equally devastating and far-reaching. From deforestation and pollution to the destruction of ecosystems, the ecological costs of warfare are profound and often overlooked. Conflicts exacerbate climate change by releasing vast carbon emissions and depleting natural resources. The aftermath of war leaves landscapes scarred, water sources contaminated, and biodiversity severely threatened. As we confront the realities of climate change, it is crucial to understand and address the environmental casualties of warfare to protect our planet for future generations.

War significantly contributes to climate change through the heavy reliance on fossil fuels to power military vehicles, aircraft, and bases. The destruction of ecosystems, such as forests and wetlands, which absorb carbon dioxide, further exacerbates the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The production of military equipment is also energy-intensive and emission-producing. For instance, a single tank can emit as much greenhouse gas as a passenger car driven for 50 years. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimated that the global military sector produced 2.1 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions in 2018, comparable to the annual emissions of Spain and Italy combined. The carbon footprint of war continues to grow, with Uppsala University reporting a 60% increase in the US military’s carbon footprint between 2001 and 2018, driven by conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan and the increasing use of drones and other military technologies. These examples underscore a pattern observed in numerous historical and contemporary conflicts, where the environmental costs are substantial and often overlooked.

The table below highlights notable conflicts throughout modern history, detailing their significant environmental impacts and how each has contributed to climate change through deforestation, pollution, resource depletion, and ecosystem destruction.

| War/Conflict | Years | Environmental/Climate Change Impact |

| World War I | 1914-1918 | Large-scale deforestation, destruction of ecosystems, pollution from chemical weapons, and emissions from industrial warfare. |

| World War II | 1939-1945 | Massive resource extraction, deforestation, destruction of habitats, nuclear fallout, and significant carbon emissions. |

| Korean War | 1950-1953 | Deforestation and soil erosion due to heavy bombing and chemical defoliants, disruption of agricultural lands. |

| Vietnam War | 1955-1975 | The use of Agent Orange leads to deforestation, loss of biodiversity, soil contamination, and long-lasting ecosystem damage. |

| Gulf War | 1990-1991 | Oil spills and fires led to air and water pollution, soil contamination, and significant carbon emissions. |

| Iraq War | 2003-2011 | Destruction of infrastructure, increased carbon emissions, pollution, and desertification due to military operations. |

| Afghanistan War | 2001-2021 | Forest degradation, water pollution, and increased desertification due to prolonged conflict. |

| Russia-Ukraine War | 2022-present | Destruction of agricultural land, water contamination, damage to nuclear facilities, and increased emissions from military actions. |

| Israel-Hamas War | 2023-present | Environmental degradation through urban destruction, water scarcity issues, and increased emissions from weapon use. |

Research increasingly highlights the vital link between resource scarcity, environmental degradation, and the outbreak of conflicts. Wars are not only fueled by competition over dwindling natural resources but also result in severe ecological damage. According to the U.N. Environment Program, 40% of wars within states over the past 60 years have been tied to natural resources, and such conflicts are twice as likely to reignite within five years after they end. As climate change worsens, its effects—ranging from displacement to damaged ecosystems—heighten the risk of conflict while widening the financial gap for climate adaptation efforts. The financial gap involves domestic spending, international aid, and private-sector finance.

The financial needs of developing countries are now 10-18 times greater than the current international public finance flows (UNEP, Adaptation Gap Report, 2023).

As climate change intensifies, its impacts on vulnerable communities disrupt livelihoods and heighten the risk of conflict. In countries where climate change leads to drought, reduced harvests, or the destruction of critical infrastructure, displaced populations face increased instability Hubbard, K. (2021, October 29). For instance, in Afghanistan, reduced harvests have driven people into poverty, making them more vulnerable to recruitment by armed groups. Similarly, across parts of Africa, shifting grazing patterns due to changing climate conditions have sparked conflict between farmers. As Hubbard noted, these examples illustrate how climate-related disruptions can escalate into violence and social unrest.

Environmental Impact of Military Operations: Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Long-Term Damage

Military operations are significant drivers of environmental degradation due to their extensive use of fossil fuels and energy-intensive equipment. The burning of fossil fuels to power military transportation and equipment—such as aircraft, naval vessels, and tanks—leads to substantial greenhouse gas emissions, including carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and nitrous oxide (N₂O). These emissions contribute to global warming and climate change. Additionally, military activities release pollutants like carbon monoxide, particulate matter, and nitrogen oxides (NOx), exacerbating air quality issues and contributing to phenomena such as acid rain and smog.

We need to increase our focus on evaluating the environmental impact of military activities

U.S. Marine Corps amphibious assault vehicles give off tactical smoke as they approach Langham Beach, Queensland, Australia, during the annual Talisman Sabre exercise, which has been criticized for its environmental impact. Picture credit: Conflict and Environmental Observatory, US Navy (2019).

The environmental impact of military operations extends beyond emissions. Artillery strikes, air and drone strikes, and the use of rockets and landmines cause immediate pollution, destroy forests, and render farmland unusable. Explosives and chemical weapons introduce toxic substances into the environment, which can persist for decades, causing long-term soil and water contamination. Landmines and unexploded ordnance further degrade land, making it hazardous and unfit for agriculture or habitation. These factors highlight warfare’s complex and enduring environmental challenges, complicating efforts to address climate change and preserve ecological stability.

The first year of the war in Ukraine alone resulted in a dramatic increase of 120 million tons of greenhouse gases, equivalent to the annual emissions of Singapore, Switzerland, and Syria combined (Reuters, 2023). This staggering statistic underscores the severe environmental impact of military conflicts. Globally, military activities and the industries supporting them account for approximately 6% of all greenhouse gas emissions. This significant figure highlights a major gap in climate accountability, as high military spenders like the US, China, UK, Russia, India, Saudi Arabia, and France often fail to report or disclose their military carbon emissions accurately (Reed, The Guardian, Nov. 2021). The lack of transparency in reporting military emissions not only obscures the full extent of their environmental impact but also impedes efforts to meet global climate targets outlined in the Paris Agreement.

Israel-Hamas war; Image Credit: Getty image

Moreover, even in peacetime, military operations contribute substantially to fossil fuel consumption. For example, the US Department of Defense’s extensive infrastructure, including 566,000 buildings across nearly 800 bases, is responsible for 40% of its fossil fuel use (McCarthy, Global Citizen, April 6, 2022). Military vehicles, particularly in conflict zones, burn large quantities of petroleum-based fuels, emitting hundreds of thousands of tons of pollutants, including carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and CO2. These emissions exacerbate climate change and pose significant health risks to civilians and military personnel (Watson Institute, Costs of War, Nov. 2019). The broader consequences of military conflicts include extensive displacement, with post-9/11 wars forcibly displacing at least 38 million people, surpassing the total displaced by all wars since 1900, except for World War II. The cumulative environmental damage and human cost of war highlight the urgent need for greater transparency and action to address the environmental and humanitarian crises fueled by military operations.

Infrastructure Vulnerability, Cybersecurity Risks, and State Instability

The destruction of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant Dam located in the Kherson region of Ukraine (The city is currently under Russian occupation) has indeed had severe environmental and economic impacts. The flooding has affected villages, agricultural lands, and irrigation systems, leading to significant crop failures12. The immediate damage has been estimated at around $14 billion. At the same time, the long-term costs of cleanup and infrastructure repair could be substantial, potentially exceeding $485 million (BBC. Ukraine dam: What we know about Nova Kakhovka, 08 June 2023).

Furthermore, ongoing cleanup and infrastructure repair costs could exceed $486 billion over the next decade, underscoring the protracted financial burden of environmental remediation in conflict zones.

Destruction of the Kakhovka Dam, Ukraine

Similarly, the 2021 cyberattack on the Oldsmar Water Treatment facility in Florida, USA, starkly highlighted the intersection of climate-induced disasters and cyber vulnerabilities. This attack, which sought to alter the chemical composition of the water supply, underscores how climate change-related disasters, such as hurricanes and wildfires, can weaken infrastructure and increase susceptibility to cyber threats. As governments and organizations grapple with the compounded stress on resources and infrastructure, critical systems become more exposed to cyberattacks, posing severe risks to public health and safety (The New York Times, February 8, 2021; Hackers Attempted to Contaminate Water Supply in Florida Town).

The case of Syria illustrates how prolonged climate stress can precipitate state instability. The severe drought from 2006 to 2010 devastated agriculture, driving mass migration and contributing to social unrest. This unrest eventually escalated into the Syrian Civil War, highlighting how climate change can exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and lead to significant regional and global security issues (Atlantic, 2015; The Syrian Civil War and Climate Change).

The Environmental Cost of Military Spending: Linking Defense Budgets to Climate Change and Environmental Degradation

The financial burden of war extends beyond economic costs, profoundly impacting the environment through military operations and defense infrastructure. The vast financial resources allocated to military spending impact economic structures and have profound environmental consequences.

Collateral Damage: The Environmental Cost of Ukraine War-Yale; Image Credit: Getty Image

In 2023, global military expenditure reached a record high of $2.443 trillion (SIPRI Fact Sheet April 2024: Trends in world military expenditure, 2023). This represents a 6.8% increase from the previous year, marking the steepest year-on-year rise since 2009. The increase in spending is primarily attributed to the ongoing war in Ukraine and escalating geopolitical tensions in regions such as Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East. Contemporary warfare is dominated by aviation. The defense budgets of major military powers reveal substantial financial commitments to military operations, raising critical concerns about the intersection of climate change and war. The countries listed in the following table—particularly the United States, Russia, and China—allocate massive resources to defense, with the U.S. alone spending $857.9 billion in 2023 (U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services, FY23 NDAA Summary). These defense expenditures represent a significant investment in activities that directly and indirectly contribute to environmental degradation and climate change (Wilson Center, Macrotrends). The reliance on fossil fuels for military vehicles, aircraft, and naval fleets contributes to high emissions, exacerbating global warming. As countries like the U.S., China, and Russia maintain their large military budgets, their responsibility for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from military sectors also grows, highlighting the environmental impact of these financial allocations (Wilson Center, Macrotrends, U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services).

Military operations are among the most energy-intensive activities globally, with defense activities reliant on vast amounts of fossil fuels. The production, maintenance, and operation of military equipment and supporting infrastructure lead to substantial carbon footprints. During wartime, emissions surge as energy consumption intensifies. With their significant defense expenditures, the United States, China, and Russia contribute heavily to this environmental burden, as evidenced by their growing military emissions. This environmental strain is expected to increase as military spending rises (Macrotrends, SIPRI).

The allocation of resources to defense also highlights the opportunity cost of such spending. Instead, billions of dollars that could be invested in renewable energy and climate initiatives are funneled into military budgets. Nations such as the U.K., with $76.9 billion in 2023, and India, with $83.6 billion in 2023, divert funds away from potential investments in sustainable development (SIPRI, The Economic Times News). A more balanced approach, where part of these resources is redirected toward climate resilience projects, could significantly impact global efforts to combat climate.

The table below highlights the vast financial resources dedicated to defense spending by major global powers, with the United States leading at $857.9 billion in 2023. From my analysis, it becomes clear that this heavy allocation toward military operations drives geopolitical influence and has significant environmental implications, particularly in emissions and climate change exacerbation.

The table below illustrates how various major military powers allocate their defense budgets.

| Country | Defense Budget (Year) | Amount (USD) | Source |

| United States | 2023 | $857.9 billion | U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services, FY23 NDAA Summary |

| Russia | 2023 | $160 billion | Wilson Center, Russia’s War Budget |

| China | 2022 | $292 billion | Macrotrends, China Military Spending |

| United Kingdom | 2023 | $76.9 billion | Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI); UK Defense Budget; second highest spender in NATO after the United States |

| India | 2023 | $83.6 billion | The Economic Times News, India Military Spending |

| France | 2022 | $53.64 billion | Macrotrends, France Military Spending |

| Israel | 2022 | $23.41 billion | Macrotrends, Israel Military Spending |

The above table shows that enormous financial commitments made by countries for defense could be redirected, at least partially, toward addressing climate change. Moreover, given the military sector’s significant environmental impact, countries’ substantial defense expenditures could be redirected to combat climate change. Globally, military activities account for around 5.5% of total greenhouse gas emissions, ranking them the fourth largest emitter if considered a single entity, behind China, the United States, and India (The Conversation, Nov 13, 2023).

The Legacy of War and Climate Change: How Past Conflicts Fuel Modern Environmental Crises

From World War I and II, through the Vietnam and Gulf Wars, to recent conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria, the legacy of warfare includes extensive ecological damage and financial costs. As climate change exacerbates resource scarcity, the legacy of past conflicts highlights the profound link between warfare and environmental degradation.

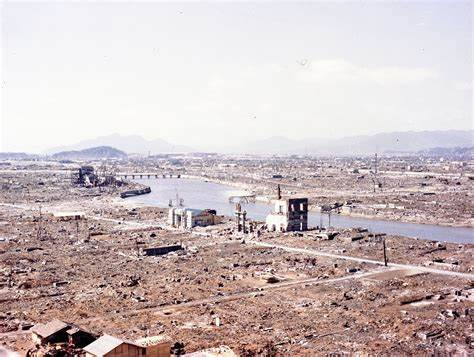

Ground view of Hiroshima, Japan: 75 years after the atomic bombing

Image credit: Washington Post

The above-mentioned wars exemplify how industrialized warfare polluted the environment and contributed to long-term climate problems. These wars caused extensive ecological damage and set the stage for future climate crises.

West Africa is widely cited as a hotspot for climate change and insecurity. According to an article published by Climate Diplomacy, there are four established ‘pathways’ of climate insecurity: worsening livelihood conditions, increasing migration and changing pastoral mobility patterns, tactical considerations by armed groups, and elite exploitation of local grievances. Each pathway illustrates distinct mechanisms by which climate change exacerbates violent conflict, particularly in vulnerable regions like West Africa. These factors do not operate in isolation but often interact, fueling a cycle of insecurity and instability (Climate Diplomacy, February 28, 2022). These pathways are valuable lenses for understanding how climate change exacerbates violent conflict in West Africa and other parts of the planet. Addressing these issues requires a holistic approach that includes improving climate resilience, promoting sustainable livelihoods, and fostering inclusive governance. Only by tackling the root causes of climate insecurity can we hope to break the cycle of conflict and build a more stable and prosperous future for the region.

The ongoing conflicts between Israel and Hamas and Russia and Ukraine could leave profound and interlinked legacies of instability, economic disruption, and environmental damage that contribute to the worsening climate crisis. If the Israel-Hamas war escalates, it may lead to broader regional instability, severe humanitarian crises, and extensive environmental degradation, setting the stage for persistent climate-related problems due to damaged ecosystems and resource depletion. Similarly, a prolonged Russia-Ukraine war could result in widespread economic disruption, geopolitical realignments, and significant environmental harm, compounding existing climate challenges through increased emissions and further environmental degradation. Both conflicts underscore the urgent need for comprehensive strategies to address the intertwined issues of warfare and climate change, as their impacts threaten to perpetuate and exacerbate the climate crisis, creating a cycle of never-ending environmental and humanitarian challenges.

Assessing the Environmental Footprint of Military Operations and Advancing Sustainable Practices

Military operations have long been a significant contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions, primarily through the extensive use of fossil fuels like jet fuel and diesel and the production of weapons and ammunition. However, with growing awareness of the environmental consequences, some military forces are beginning to adopt sustainable practices. Despite these initial efforts, achieving substantial reductions in emissions requires more comprehensive action, global cooperation, and the integration of environmental concerns into military strategies.

Military activities contribute to global emissions by consuming fossil fuels, such as jet fuel and diesel, and manufacturing weapons and ammunition. Combat operations intensify these emissions due to increased fuel and resource demands. For instance, military aircraft account for 8-15% of the aviation sector’s 3.5% share of global warming, and military-driven marine activities contribute to 2.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions (Cottrell & Darbyshire, 2021).

In response, some militaries, like the U.S. Army, implement energy-efficient technologies, renewable energy sources, and sustainable building standards such as LEED for new infrastructure projects (Military and Climate Change: Total Military Insight, 2024). These initiatives include improving logistics to lower fuel use, reducing waste, and promoting environmental stewardship through training programs. However, significant challenges remain. Achieving meaningful reductions in military emissions will require broader adoption of sustainable practices, increased investments in green technologies, and integration of environmental considerations into military operations (Cottrell & Darbyshire, 2021).

Economic Decline, Emerging Crisis Zones, and Humanitarian Dependence

The long-term economic decline from continuous conflict and resource scarcity significantly impacts recovery efforts. Countries facing prolonged instability often rely heavily on international humanitarian aid, hindering self-sufficiency and financial recovery. Reports from various international organizations highlight that nations such as Yemen, Venezuela, South Sudan, and Haiti have experienced substantial economic declines due to ongoing conflicts and resource scarcity, resulting in severe drops in GDP, unemployment, and pervasive poverty. The destruction of infrastructure in these countries complicates recovery efforts, underscoring the urgent need for international support and sustainable solutions.

Countries like Sudan, Nigeria, Syria, and Afghanistan exemplify the challenges linked to conflict-induced resource scarcity and terrorism. These regions experience resource competition, population displacement, and significant humanitarian crises. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reported in 2023 that around 120 active armed conflicts worldwide involve over 60 countries and numerous non-state armed groups, highlighting the global scale of the crisis and the extensive need for emergency aid (ICRC Reports, June 10, 2022; International Committee of the Red Cross).

The Climate-Election Nexus: A Critical Overview

In 2024, the world is witnessing an unprecedented surge in elections, with citizens across at least 64 countries casting their votes for national leaders. (World Resources Institute, Aug. 20, 2024). This landmark year highlights the growing prominence of climate change in political platforms, signaling a pivotal shift towards integrating environmental issues into governance. As election outcomes unfold, the global focus on climate change will intensify, shaping national and international policies. The decisions made by newly elected leaders will critically influence global climate action, impacting the effectiveness of future environmental strategies and the pace of addressing climate crises.

This electoral wave is steering climate policies and affecting economic and international dynamics. Leaders prioritizing climate action will likely bolster commitments to global agreements like the Paris Accord and enhance support for international climate finance. Conversely, less ambitious agendas could impede global climate progress. Furthermore, elections that highlight climate-focused policies often lead to economic growth through investments in green technologies and sustainable practices. Youth engagement and recent climate disasters have amplified voter demand for robust climate action, underscoring the urgency for effective climate policies and continuous advocacy to address these complex challenges.

The Effects of War on Global Food Security and Environmental Well-being

War significantly undermines global food security by disrupting agricultural production and supply chains. The destruction of farms, food storage facilities, and infrastructure during conflicts leads to widespread hunger and malnutrition. For example, the war in Ukraine has severely impacted food prices, notably in Egypt, where domestic food prices have surged by over 30% due to disrupted supply chains (Welsh, 2023). In the UK, climate change, exacerbated by extreme weather events, contributed to a 5.3% increase in food price inflation in 2023, highlighting how climate impacts also compound food security issues (Harwatt & Aylett, 2024). Such disruptions reveal food systems’ vulnerability to environmental and conflict-related stresses.

Beyond immediate food shortages, wars often exacerbate long-term food insecurity beyond immediate food shortages by destabilizing economies and increasing inflation, further limiting access to available food. Armed groups may loot and destroy agricultural resources, perpetuating a cycle of deprivation and violence. Additionally, conflicts drive global fertilizer prices due to increased natural gas costs, affecting agrarian productivity worldwide (The Conversation, 2023). The environmental consequences of war, such as air pollution, deforestation, and soil degradation, also impact food production and safety. Floods and landmines, particularly in war-torn regions, exacerbate soil degradation and pose risks to agricultural lands.

The environmental and health impacts of war are profound. Depleted uranium, used in military ammunition and armor, presents severe health risks due to its chemical and radiological properties. Its use in conflicts has led to significant environmental contamination and health issues, such as kidney damage and radiation exposure, with over 1,000 tons deployed in the Second Gulf War alone (Harvard International Review, 2021). The lack of consideration for environmental impacts in war strategies highlights the urgent need for comprehensive approaches to mitigate the ecological and health damages caused by military conflicts.

From the South China Sea to the Arctic: How Geopolitics Fuels Environmental Decline

Geopolitical tensions often exacerbate environmental degradation, creating a cycle where strained political relationships lead to unsustainable exploitation of natural resources and worsening environmental conditions, which fuels further conflict. One prominent example is the South China Sea dispute, where several nations vie to control maritime territories rich in oil and gas reserves. This has led to aggressive overfishing, coral reef destruction, and pollution due to military activities, all of which have had significant ecological impacts.

Political instability and conflicts over water resources in regions such as the Tigris-Euphrates and Nile River basins have intensified environmental degradation in the Middle East. In Syria, prolonged drought and the unsustainable use of agricultural land have been linked to the rise in civil unrest, illustrating how environmental stress can fuel geopolitical instability. Furthermore, geopolitical interests in the Arctic are increasing due to melting ice caps, which are opening new shipping lanes and making previously untapped oil and gas reserves accessible. Countries like Russia, the United States, and China are intensifying their presence in this ecologically sensitive area, raising concerns over environmental damage and increased geopolitical rivalry.

The Dual Crisis: Humanitarian and Environmental Consequences of Modern Wars

The scale of ongoing wars such as Ukraine-Russia and Israel-Hamas has reached levels not seen since World War II, with deaths hitting a 28-year high. Amidst the immediate humanitarian crisis, it’s crucial not to overlook the environmental devastation wrought by warfare. As Yahya Arhab highlights in The Conversation (2023), these wars are more than just human tragedies—they are ecological catastrophes. The destruction from ongoing conflicts—ranging from severe pollution and contaminated water sources to deforestation and hazardous waste—exacerbates climate change. Military operations significantly increase greenhouse gas emissions and contribute to the degradation of vital ecosystems, compounding the climate crisis. Additionally, the potential use of nuclear weapons poses a severe threat, with risks of radioactive contamination and the possibility of a “nuclear winter,” further intensifying the environmental crisis. These conflicts are not isolated events but powerful drivers of a global ecological catastrophe, underscoring the urgent need to address their long-term impacts on people and the planet.

The Precipitous Future: The Interconnected Impact of War and Climate Change on Environmental and Human Systems

Wars have profound and often devastating environmental consequences, such as deforestation, soil degradation, and widespread pollution from weaponry. For instance, the Vietnam War led to extensive deforestation due to the use of Agent Orange, which has left lasting scars on the natural world. Climate change compounds these effects by amplifying the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, like floods and heat waves. Such events can trigger the exposure of landmines and unexploded ordnance, heightening risks for affected communities, as seen in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where floods have unearthed landmines from past conflicts.

Climate-induced resource scarcity—affecting essential resources like water and food—can intensify conflicts and exacerbate existing tensions. In Syria, prolonged droughts have been linked to the onset of civil unrest, illustrating how environmental stress can fuel geopolitical instability. Both warfare and climate change contribute to mass displacement, as people are forced to flee their homes, putting additional strain on resources in host communities and further destabilizing social and political systems. The Sahel region’s displacement crisis, driven by conflict and climate change, exemplifies this dual threat.

Climate Change as a Unifying Force: Potential and Pitfalls

As climate change emerges as a defining global challenge, it presents opportunities and risks akin to historical phenomena like nationalism. Just as nationalism once forged unity within nations, climate change has the potential to foster global solidarity as countries face a shared existential threat. However, this potential for collective action is tempered by the complex ways climate impacts can exacerbate existing conflicts and regional tensions. Understanding these dynamics is essential for navigating the future of international cooperation and conflict resolution in the face of climate change.

Research from the RAND Corporation highlights that while climate change can drive collective global responses, it acts as a “threat multiplier,” intensifying existing conflicts and instability. Their 2024 study, using a blend of climate assessments and machine learning techniques, reveals that, though secondary to issues such as governance and economic hardship, climate factors still play a significant role in shaping future conflict risks. For instance, countries like Iraq, Yemen, and Pakistan are particularly vulnerable to climate-induced stresses like drought, which could heighten conflict risks. Additionally, simulations of drought impacts suggest that climate-related factors might worsen conflict scenarios in ways not yet fully captured by current models (RAND National Security Research Division, 2024).

On the other hand, some scholars, including Daniele Conversi, argue that climate change could serve as a rallying cause for global unity, like how nationalism unified populations within nations. Conversi (2020) posits that the universal nature of climate change might foster a new form of global solidarity, potentially reshaping international relations and security paradigms. Nonetheless, the intricate interplay between climate impacts and socio-economic factors highlights the need for comprehensive strategies to effectively understand and address climate-related security threats.

Global Efforts in Environmental Restoration and Peacebuilding

In recent years, comprehensive peace agreements and restoration projects have demonstrated a significant shift towards integrating environmental considerations into conflict resolution and recovery efforts.

One of the most notable examples is Colombia’s Peace Accord, a pioneering approach that addresses conflict’s social and political dimensions and the extensive environmental damage caused by decades of violence. The accord includes a variety of measures aimed at mitigating environmental harm, such as reforestation initiatives, sustainable land management practices, and enhancing community involvement in environmental decisions. Notably, over 20% of the accord’s commitments are dedicated to ecological concerns, categorized into four key areas: adapting to and responding to climate change, preserving natural resources and habitats, protecting environmental health through access to clean water, and ensuring community participation in decision-making regarding rural programs and resource management (The Conversation, May 14, 2024).

In Afghanistan, international organizations and NGOs have undertaken significant restoration projects to rehabilitate land and improve water management in the aftermath of conflict. These initiatives focus on rebuilding agricultural productivity and mitigating the environmental impacts of prolonged conflict, contributing to the overall recovery and sustainability of affected regions.

Similarly, Peru’s Glaciares+ project exemplifies effective environmental conservation in mountainous regions. This initiative focuses on preserving high mountain ecosystems crucial for water regulation and provision across the country. The Glaciares+ project fosters collaboration between communities, public institutions, and private entities by integrating local and Indigenous knowledge into risk and water resource management. The project has significantly enhanced disaster risk management capabilities, developed new early warning systems for landslides, and benefitted nearly 70,000 people by improving their resilience to climate-related hazards.

Photo credit to Un Environment Program (Integrating Indigenous knowledge is critical to protecting mountain ecosystems. Photo by UNEP/ Gregorio Ferro.

Drought-Resistant Crops in Syria: In response to the severe droughts exacerbated by conflict, Syrian farmers have been provided drought-resistant crop varieties and training in sustainable farming practices. This helps ensure food security and reduces the strain on water resources.

Community-Based Adaptation in Sudan: In Sudan, community-based adaptation projects focus on building resilience to climate change and conflict. These projects include the construction of water harvesting structures, reforestation, and introducing climate-resilient agricultural practices.

Military Emissions Reporting for Climate Action

Military emissions reporting is complex and often opaque. While some countries voluntarily report their military greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, many do not. This is primarily due to historical exemptions and voluntary reporting standards. For example, the United States, Russia, China, India, Saudi Arabia, and Israel have significant military budgets that do not consistently report their military emissions (The Conversation, Nov. 2021).

The 2015 Paris Agreement removed Kyoto’s military exemption but left military emissions reporting voluntary. This means that many countries either under-report or aggregate military emissions with other sectors, making it difficult to understand their environmental impact accurately. Currently, 46 countries and the European Union must submit yearly reports on their national emissions under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The UNFCC mandates annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reporting by its signatories, but military emissions reporting remains voluntary and often lacks transparency. Current military GHG data is frequently incomplete, highlighting the need for more comprehensive reporting to manage and reduce emissions effectively. NATO’s Climate Change and Security Action Plan marks progress by outlining a methodology for measuring military emissions and setting voluntary reduction goals. However, more action is needed to address other environmental concerns, such as equipment lifecycle, supply chain management, waste reduction, and environmental protection during military operations. As signatories of the Paris Agreement, NATO Allies acknowledge the urgent need for climate action and aim to limit global warming to below 2°C, preferably 1.5°C, above pre-industrial levels.

Lessons Learned and Future Predictions on War and Climate Change

Recent conflicts underscore several crucial lessons about the interplay between war and environmental degradation. One significant takeaway is the necessity for peace accords to explicitly address ecological harm as a considerable consequence of war. Recognizing that a healthy environment is fundamental to sustainable livelihoods and lasting peace is essential. This includes mitigating pollution and contamination from attacks on industrial facilities, explosive remnants, chemical spills, and military activities that release toxic substances. Moreover, addressing the destruction of ecosystems—such as deforestation and wildlife harm—and the emission of greenhouse gases from military operations is vital for future conflict resolution efforts.

For example, the peace accords in Colombia have demonstrated the importance of integrating environmental provisions with other critical issues, such as rural reform and political participation. These accords include clear goals for rebuilding infrastructure and institutions, assigning responsibilities, and setting timelines, which help prioritize environmental restoration. Similarly, international efforts, such as the $66 billion pledged by foreign donors for rebuilding Ukraine, highlight the role of strict environmental standards in financial aid (RAND National Security Research Division, 2024).

Looking ahead, the involvement of local communities in environmental restoration is crucial. Their engagement ensures that restoration efforts are tailored to the specific needs of affected areas and fosters a sense of ownership and responsibility. Local knowledge and resources can significantly enhance the effectiveness of these efforts.

Future predictions suggest that while reconstructing nations and regenerating ecosystems post-war is challenging, it also presents an opportunity to build a more sustainable future. Case studies like Ukraine and Gaza could provide valuable insights into managing the environmental impacts of war and developing strategies for more resilient recovery.

Conclusion

The compounded effects of war on the environment escalate climate change and strain global resources and health systems, creating long-term challenges for recovery and sustainability. Recognizing environmental harm as a significant consequence of war is crucial for mitigating extensive damage and further climate crises. Integrating environmental provisions into peace accords, as seen in the Colombia Accords, can foster sustainable and equitable conditions for reestablishing democracy. The international community must be crucial in monitoring and verifying environmental restoration, providing financial and technical support, and ensuring ecological restoration remains a priority.

Ongoing conflicts, such as those in the Middle East and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, have profound environmental consequences that are often underestimated. The destruction of infrastructure during war disrupts economies, leading to state instability and social unrest. Addressing the interconnected threats of war and climate change requires immediate and decisive action from all levels of society. By reallocating defense expenditures towards climate initiatives, nations can make significant strides in addressing climate change while reducing their carbon footprints.

Local communities play a pivotal role in environmental restoration after the war. Their involvement ensures that restoration efforts are tailored to the specific needs of affected areas, fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility. Additionally, depleted uranium poses significant environmental and health risks, making it an environmental justice issue that requires rigorous scrutiny. By integrating ecological considerations into conflict resolution strategies and involving local communities, we can work towards a more sustainable and peaceful future, ensuring that future generations inherit a world where peace and environmental health are safeguarded. Peace accords must explicitly address ecological harm as a significant consequence of war, integrating environmental restoration with other issues like rural reform and political participation and involving local communities to ensure sustainable and equitable rebuilding efforts.

List of References:

- Atlantic. (2015). The Syrian Civil War and climate change. Retrieved from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/

- BBC, 8 June 2023. Ukraine dam: What we know about Nova Kakhovka https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-65818705

- Brown University, Watson Institute. (2019). Costs of war: Environmental and human costs of war. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/social/environment

- Conversi, D. (2020, March 23). The ultimate challenge: Nationalism and climate change. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/nationalities-papers/article/abs/ultimate-challenge-nationalism-and-climate-change/1667FAD7F2731F536AA671C42C8E99C3

- Cottrell, L., & Darbyshire, E. (2021, June 16). The military’s contribution to climate change. Conflict and Environment Observatory. https://ceobs.org/the-militarys-contribution-to-climate-change/

- Climate Diplomacy. (2022, February 28). Climate change and violent conflict in West Africa: Assessing the evidence. https://climate-diplomacy.org/magazine/conflict/climate-change-and-violent-conflict-west-africa-assessing-evidence

- Glaciares+. (2024). Glaciares+ Project: Conservation and risk management in Peru. Retrieved from https://www.care.org/our-work/food-and-nutrition/water/glaciares/

- Harvard International Review (HIR). (2021). Depleted uranium, devastated health: Military operations and environmental injustice in the Middle East. Retrieved from https://hir.harvard.edu/depleted-uranium-devastated-health-military-operations-and-environmental-injustice-in-the-middle-east/

- Hubbard, K. (2021, October 29). Global warming risks increase in conflicts. US News. https://www.usnews.com

- ICRC Reports. (2022, June 10). International Committee of the Red Cross: Conflict and humanitarian crisis. Retrieved from https://www.icrc.org/en/report/icrc-annual-report

- McCarthy, J. (2022, April 6). Military fossil fuel usage. Global Citizen.

- Military and Climate Change: Total Military Insight. (2024, July 24). Military strategies for sustainable development. Retrieved from https://totalmilitaryinsight.com/military-strategies-for-sustainable-development/

- RAND. (2024, March 15). How climate change will affect conflict and U.S. military operations. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/articles/2024/how-climate-change-will-affect-conflict-and-us-military.html

- Reed, B. (2021). The world’s militaries avoid scrutiny over emissions. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/11/worlds-militaries-avoiding-scrutiny-over-emissions

- SIPRI. (2019). Trends in world military expenditure, 2023. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/report/world/sipri-fact-sheet-april-2024-trends-world-military-expenditure-2023-encasv

- SIPRI Fact Sheet. (2024, April). Trends in world military expenditure, 2023. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/report/world/sipri-fact-sheet-april-2024-trends-world-military-expenditure-2023-encasv

- The Conversation. (2023, November 13). Conflict pollution, washed-up landmines, and military emissions – here’s how war trashes the environment. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/conflict-pollution-washed-up-landmines-and-military-emissions-heres-how-war-trashes-the-environment-216987

- The Conversation. (2024, May 14). Colombia’s peace accord: A comprehensive approach to environmental restoration. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/wars-cause-widespread-pollution-and-environmental-damage-heres-how-to-address-it-in-peace-accords-214624

- The Conversation. (2021, November 9). How the world’s militaries hide their huge carbon emissions. https://theconversation.com/how-the-worlds-militaries-hide-their-huge-carbon-emissions-171466

- Tarif, K. (n.d.). Climate change and violent conflict in West Africa: Assessing the evidence. Environmental Research Letters. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa6f7b

- United Nations. (2024, August). Darfur: An update on the crisis. Retrieved from https://press.un.org/en/2021/sgsm20827.doc.htm

- United Nations Environmental Program. (2023). Adaptation gap report. Retrieved from https://www.unep.org/resources/adaptation-gap-report-2023

- Welsh, C. (2023). Russia, Ukraine, and global food security: A one-year assessment. Center for Strategic International Studies (CSIS). Retrieved from https://www.csis.org/programs/global-food-and-water-security-program/topics/russia-ukraine-war-and-global-food-security

- World Resources Institute. (2024, August 20). The biggest year in modern history for global elections. https://www.wri.org/insights/climate-elections-2024