Introduction

The Brahmaputra River, one of the world’s most potent waterways, sustains millions of people across China, India, and Bangladesh. As a critical lifeline for agriculture, livelihoods, and ecosystems, its future is now at the center of a geopolitical storm. China’s ambitious plan to construct the world’s largest hydropower dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo—the river’s Tibetan stretch—raises serious concerns about water security, ecological balance, and regional stability. With the potential to generate unparalleled hydropower, the project risks disrupting fragile ecosystems and intensifying tensions between neighboring nations.

This blog explores the multifaceted implications of the hydropower project, examining its environmental, economic, and geopolitical impact on South Asia and the broader Indo-Pacific region. It delves into the significance of transboundary rivers and their global implications, the role of United Nations water conventions in managing shared water resources, and the importance of international agreements for cooperation. Additionally, we analyze India’s concerns, China’s collaboration with other nations on transboundary river dam projects, and the delicate balance between economic progress and environmental sustainability..

Beyond the immediate geopolitical concerns, large river dams have historically been crucial for modern development, providing energy, irrigation, and economic benefits. However, they also pose risks, including catastrophic failures and long-term environmental consequences.

This blog further explores the concept of water as a weapon—how nations have historically used water control as a strategic advantage—and the need for a robust framework for transboundary water management. As climate change and increasing water demand pressure on global resources, understanding these dynamics is essential to fostering cooperation and preventing future conflicts over shared waterways like the Brahmaputra.

The Brahmaputra River: A Transboundary Lifeline and a Powerhouse of Hydropotential

The Brahmaputra River, a majestic transboundary river, starts from the Chemayungdung Glacier at 17,090 feet in Tibet, China. Known as the Yarlung Tsangpo in China, it flows through China, India, and Bangladesh and receives contributions from Bhutan. The river spans 1,800 miles and is the fifth-largest in the world by discharge, profoundly influencing many ecosystems. It supports livelihoods and economies while carving through densely populated, ecologically sensitive areas across its traverse regions.

Countries downstream of the Brahmaputra River, such as India and Bangladesh, face potential impacts on water availability and flow due to the dam projects being constructed upstream in China. Image Credit: The Economic Times, Oct. 05, 2016; (Why India is worried about China’s dam projects on the Brahmaputra River)

The river’s immense flow and strategic importance make it central to environmental and infrastructural discussions in the region. The proposed construction of the world’s largest dam (Medog Dam) on the Yarlung Tsangpo River could transform regional energy production forever. This dam could generate 300 billion kilowatt-hours annually, powering the yearly consumption of 300 million people (Times of India, Dec 26, 2024). Estimated at US$137 billion, this hydropower project offers unprecedented power generation potential, revolutionizing energy production in South Asia (Siow, Maria: South China Morning Post, Jan 2025).

China’s plan to construct the in Tibet has sparked significant concerns across the Indo-Pacific region, particularly in India and Bangladesh. The proposed dam threatens to alter the Brahmaputra River’s flow, affecting millions of people in India and Bangladesh who depend on its waters. It jeopardizes agriculture, drinking water, and livelihoods, posing risks to water shortages and environmental degradation. Generating vast hydropower, the project sparks fears of escalating regional geopolitical tensions. The dam’s implications could worsen fragile relations, complicating water management and regional cooperation among China, India, and Bangladesh.

This groundbreaking project, the largest of its kind, could turn the river’s waters into a new geopolitical rivalry front. The escalating tensions between China and India may worsen, making the Brahmaputra River a focal point of regional disputes. The project raises serious concerns about its environmental and social consequences, disrupting fragile ecosystems and local communities. Experts warn that while immediate conflict is unlikely, the dam increases strain on an already tense relationship between nations. Existing mistrust, border disputes, and competing interests could escalate, creating new challenges in managing shared water resources (Siow, Maria, 2025).

Brahmaputra River (The Yarlung Tsangpo), also called Yarlung Zangbo and Yalu Zangbu River, is a river that flows through the Tibet Autonomous Region of China and Arunachal Pradesh of India. It is the longest river in Tibet and the fifth longest in China. The upper section is also called Dangque Zangbu, which means “Horse River” (Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yarlung_Tsangpo).Image credit: South China Morning Post;

As a transboundary river, the Brahmaputra is crucial for providing water for agriculture, fisheries, and hydropower across multiple countries. However, it also presents water sharing and management challenges, with potential conflicts over its use and development projects. It is a lifeline for millions but requires international cooperation to ensure equitable resource access.

The Transboundary Journey and Power Potential of the Brahmaputra River

The Yarlung Tsangpo River starts its journey from Tibet, an autonomous region of China, and enters India through Arunachal Pradesh. As the river widens and flows through Assam in East India, it is commonly called the Brahmaputra. Upon entering Bangladesh, the Brahmaputra merges with tributaries, becoming the Jamuna River, the Padma, and the Meghna. It eventually flows into the Bay of Bengal, completing its vast and significant transboundary journey. The river’s high sediment load causes an abrupt shape change as it leaves the Himalayas and enters flatter terrain. This sediment contributes to the river’s dynamic nature, influencing ecosystems, agriculture, and flood patterns across its extensive course (NASA Earth Observatory).

Topography of Brahmaputra River system. Image Credit: Air University, The Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs; Authors: Neeraj Singh Manhas and Dr. Rahul M. Lad; March 12, 2024

The river slope is steep until entering India, dropping approximately 4,800 meters over 1,700 kilometers in Tibet, China. With tremendous power potential, the Brahmaputra plunges 2,000 meters (6,560 ft.) along the “Great Bend” section before entering India. This steep drop offers significant opportunities for hydropower generation, making it a key factor in the region’s energy prospects (Pasircha, Anjana, January 2025). According to a prominent Chinese science forum, the “Great Bend” has immense water resource exploitation potential. It is estimated that the energy it could generate is equivalent to 100 million tones of crude coal or the South China Sea’s combined oil and gas reserves (Anand, Brig Vinod, Feb 07, 2013). The Brahmaputra Valley has an average width of about 80 km. The Brahmaputra River is estimated to have a hydropower potential of around 70,000 megawatts, making it one of the region’s most promising rivers for energy generation.

Strategic and Geopolitical Significance of the Brahmaputra River Dam Project

The Brahmaputra River dam is significant to China due to its hydropower potential for developing western regions. It enables investment in clean energy resources, aligning with China’s strategy to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and ensure sustainability. The proposed dam is larger and more impressive than the “Three Gorges Dam,” the world’s largest hydroelectric dam. In comparison, the new project would be vastly superior in scale and capacity (Voice of America, Jan 09, 2025). The Voice of America explores how the project will prioritize ecological protection, aligning with China’s carbon neutrality goals. It further states the dam is a cornerstone of China’s “Open Up the West” campaign, promoting sustainable development in Western China. It is part of a larger initiative to enhance water resources and improve economic and environmental outcomes in the region.

The proposed Brahmaputra river dam and associated construction activities will be located in a sensitive region close to the Indian border in Tibet. The strategic and military implications of China’s presence in the area and the potential for water manipulation are a security concern for India.

The construction of the Brahmaputra river dam project allows China to control and regulate water flow from the river, which is crucial for energy generation and domestic water supply in the Tibetan region. Additionally, China may seek to divert the river to meet domestic needs, especially for irrigation. The dam’s construction may be seen as a geopolitical move to increase China’s influence over the Brahmaputra river system. It creates potential leverage over India and Bangladesh, which rely heavily on the river for water and agriculture. Both countries depend on the river for hydroelectric power, further amplifying the geopolitical implications of the project.

India’s Concerns Over the Brahmaputra River Dam Project

India has expressed deep concerns about China’s plan to construct a hydropower dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo River. The Yarlung Tsangpo flows downstream as the Brahmaputra River, a lifeline for millions in northeastern India. India fears the dam could reduce water flow during dry seasons, threatening agriculture and livelihoods in states like Assam. Changes in the river’s flow patterns could intensify seasonal flooding, worsening the destruction caused by monsoons (Times of India, Dec 26, 2024).

The geopolitical implications of this project further exacerbate India’s concerns. The Brahmaputra flows through Arunachal Pradesh, a disputed territory claimed by China as “Southern Tibet.” The construction of dams by both nations has intensified tensions over water resources. With its rivers and tributaries feeding into the Brahmaputra, Arunachal Pradesh accounts for nearly one-third of India’s total hydroelectric potential, estimated at around 150,000 megawatts (Anand, Brig Vinod, Feb. 2013). India has raised alarms about China’s potential to weaponize its control over the river to gain geopolitical leverage, particularly during the conflict. Such control threatens India and raises concerns for neighboring countries like Bangladesh, Nepal, and Myanmar, which rely on shared water resources for socio-economic stability (Samaranayake et al., 2016; Manhas et al., 2024).

Environmental and climate-related implications add another layer of complexity to India’s apprehensions. The construction of this mega-dam threatens to disrupt the river’s natural flow, reducing downstream water availability and impacting the delicate ecosystems and biodiversity of the Himalayan region. Altered water flow patterns could exacerbate water scarcity during dry months and increase the likelihood of catastrophic floods during monsoons, especially in flood-prone areas like Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. Additionally, the dam’s sediment retention, essential for maintaining soil fertility, could severely harm agricultural productivity in India’s fertile plains.

The region’s vulnerability to climate change further amplifies these environmental challenges. Melting glaciers and extreme weather events already pose significant threats, and the dam’s construction could compound these issues, creating long-term socio-economic and ecological instability. Communities dependent on the Brahmaputra for their livelihoods face an uncertain future, raising alarms about the broader implications for regional security and cooperation.

Image Credit: Exploring the Brahmaputra River Valley: A Nature Lover’s Paradise; Rhinos on safari in Kaziranga National Park, Apr 18, 2023 (https://www.assambengalnavigation.com/post/exploring-the-brahmaputra-river-valley-a-nature-lover-s-paradise)

In light of these challenges, India’s concerns are not merely about resource management but extend to safeguarding its environmental health, economic stability, and geopolitical interests in a region marked by growing tensions and ecological fragility.

India’s Response to China’s Brahmaputra River Dam Projects

In response to China’s growing influence over the Brahmaputra, India plans the Siang Upper Multipurpose Project (SUMP) to regulate the river’s flow and provide a buffer against flooding. The SUMP project includes an 11,000-megawatt hydropower capacity and a reservoir to store 9 billion cubic meters of water (Bhattacharya, 2025). India sees this project as a protective measure, ensuring water availability during dry periods and mitigating the risk of floods caused by sudden water releases from Chinese dams. However, the project has faced local protests in Arunachal Pradesh, reflecting opposition to large-scale hydropower projects in the region.

Image Credit: The Diplomat, Jan. 08, 2025; https://thediplomat.com/2025/01/indias-response-to-worlds-largest-dam-in-china-faces-local-opposition/

The growing concerns over China’s hydropower projects and India’s countermeasures highlight the complex dynamics of transboundary water management. While these projects are critical for national energy needs, they also increase geopolitical tensions and contribute to regional instability. The issue of water rights and resource management may have far-reaching implications for countries like Nepal and Bhutan, which, although not directly involved, could become entangled in disputes over water resources (Manhas et al., 2024). The dam projects and their geopolitical ramifications underscore the challenges of balancing regional development with environmental and political stability.

Bangladesh’s Concerns Over Upstream Water Management

Bangladesh, a downstream riparian nation, shares India’s concerns regarding the potential impacts of upstream dam construction on the Brahmaputra River. With approximately 70 percent of its population living in the Brahmaputra basin, any river flow alteration could result in severe consequences, such as water shortages, disruptions to agriculture, and significant impacts on livelihoods. This underscores the need for equitable water resource management among riparian countries (Manhas, Singh, & Lad, March 2024).

Bangladesh is particularly vulnerable to natural disasters, such as floods and droughts, exacerbated by upstream water practices in India and China. The country’s insufficient capacity to mitigate these challenges makes it highly susceptible to agricultural disruptions and water shortages. Additionally, historical discord between India and Bangladesh over water-sharing arrangements, such as for the Teesta River, further complicates the management of shared water resources (CNA Analysis and Solutions, May 2016).

China’s approach to the Brahmaputra issue has primarily been focused on bilateral relations with India, often neglecting to engage Bangladesh in discussions about shared water resources. Although China has signed agreements to share river flow data with India during flood seasons, it has hesitated to address basin-wide cooperation that includes India and Bangladesh. This lack of multilateral engagement disadvantages Bangladesh, leaving it vulnerable to the effects of water diversion and poor river management (Samaranayake, Nilanthi, Satu Limaye, and Joel Wuthnow. May 2016).

The United States Concerns Over the Project

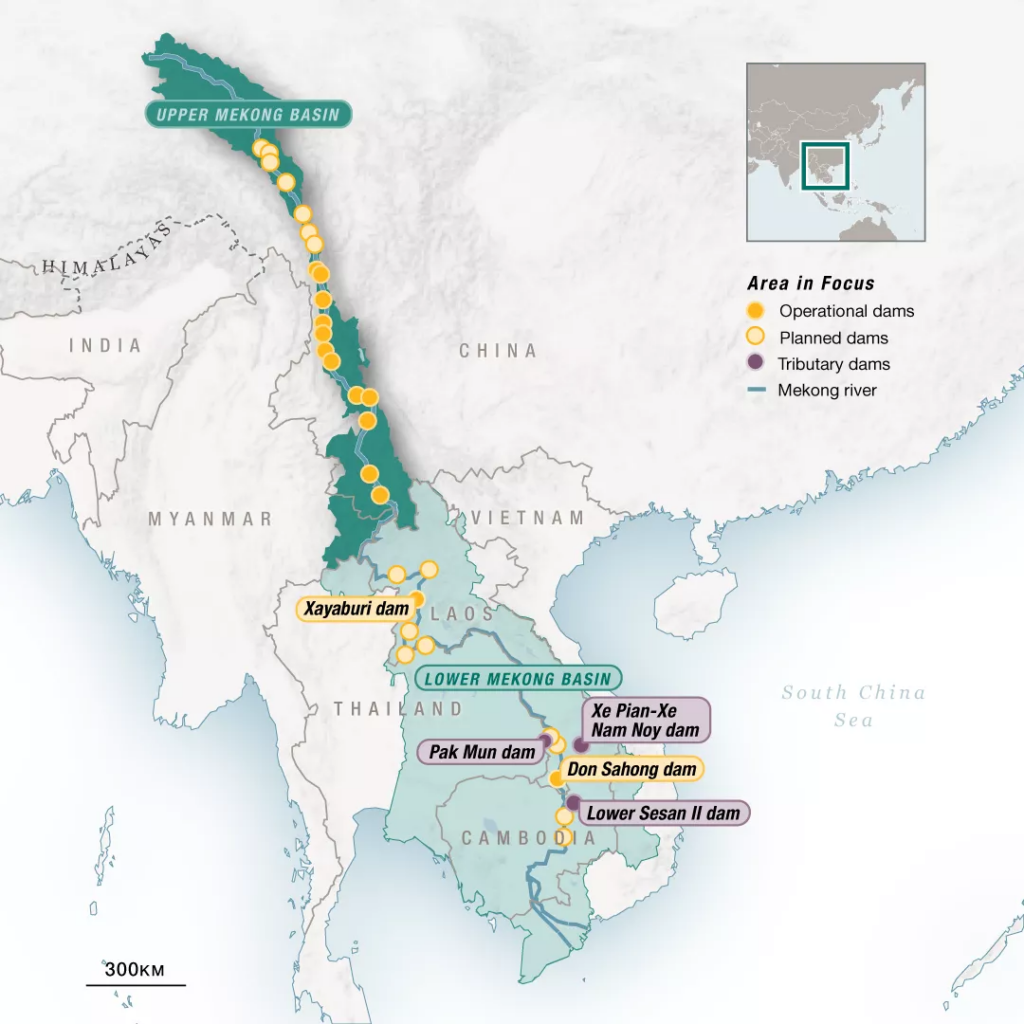

The United States has raised concerns over China’s dam construction on the Brahmaputra River, emphasizing its potential environmental and climate-related consequences. Drawing comparisons with similar developments in the Indo-Pacific region, such as the Mekong River, the U.S. highlighted how upstream dams have significantly disrupted water flow, harmed ecosystems, and negatively impacted downstream communities. These examples underline the risks associated with China’s project, raising fears about the potential ecological and societal challenges that could arise along the Brahmaputra River.

Why is the Indo-Pacific region considered critical?

The Indo-Pacific region, a vast and dynamic area, stretches from the eastern coasts of Africa to the western shores of the Americas. This expansive region includes numerous influential nations, such as India, China, Japan, Australia, and the United States, and serves as a critical hub for global trade. Key sea lanes, like the Malacca Strait and the South China Sea, are pivotal in connecting economies worldwide. Moreover, the Indo-Pacific holds immense strategic importance as it becomes a stage for geopolitical competition, with nations vying for influence and control over its valuable resources and critical waterways.

The Indo-Pacific region is considered a critical area for several reasons. Firstly, over 65% of the world’s oceans and 25% of land are vital to the planet’s ecosystem and global infrastructure. Additionally, more than half of the world’s population resides in these areas, with 58% of the youth concentrated in the region. Furthermore, this part of the world contributes significantly economically, accounting for 60% of global GDP, 65% of world trade, and driving two-thirds of global economic growth. As a result, these regions play a pivotal role in shaping the future of the environment and the global economy (iLearn CANA, October 26, 2022).

Indo-Pacific Region”, Image Credit: iLearn CANA, October 26, 2022 (https://ilearncana.com/details/Indo-Pacific-region/3716)

Potential Impacts of the Brahmaputra River Dam Project on Nepal and Bhutan

While Nepal and Bhutan are not directly downstream nations of the Brahmaputra River, both are connected to its tributaries and could experience indirect impacts from changes in its flow. Nepal, located north of India, is not a direct downstream nation of the Brahmaputra. The country’s rivers, such as the Koshi, Gandaki, and Karnali, ultimately flow into the Ganges basin rather than the Brahmaputra. However, due to the interconnected nature of regional river systems, Nepal could still be affected by alterations in the Brahmaputra’s flow, particularly regarding water availability and flood risks.

Bhutan, also located north of India, lies along the eastern section of the Brahmaputra basin. While the river does not flow directly through Bhutan, its tributaries, such as the Manas and Subansiri, do. As a result, Bhutan is indirectly impacted by the Brahmaputra’s water flow, although it is not considered a direct downstream nation.

Understanding Transboundary Rivers and Their Impacts

Most countries worldwide depend on rivers, lakes, and aquifers that either originate in or flow into neighboring nations (UN Water, 2024). According to the United Nations, a transboundary river is a river that flows through or is shared by two or more countries. As water is a shared resource between neighboring nations, these rivers often present challenges regarding water resource management, environmental protection, and cooperation.

Similarly, transboundary basins consist of river, lake, and aquifer systems shared by two or more nations. This interdependence underscores the critical need for water cooperation to advance sustainable development and tackle the challenges posed by climate change. The 2024 UN-Water report highlights the critical global importance of transboundary waters, noting that approximately 313 rivers and lakes and 468 aquifers cross international borders. It emphasizes that water resources originating in or flowing into neighboring countries are essential for 153 UN Member States. Moreover, transboundary rivers alone account for 60% of the world’s freshwater supply, with the basins of these rivers and lakes sustaining the lives and livelihoods of more than three billion people.

The UN defines transboundary waters in the context of the UN Watercourses Convention, which establishes principles for cooperation, equitable use, and protection of international watercourses. These principles encourage countries to share water resources equitably, prevent pollution, and engage in joint management efforts.

Transboundary river water is essential for sustainable development and global water security, serving 2.8 billion people, covering 42 percent of the Earth’s surface, and flowing through 153 countries. However, these waters are often unsustainable, and increasing pressures from population growth, agriculture, energy production, ecosystem degradation, and climate change are expected to exacerbate the situation (United Nations Economic and Social Council. August 2024).

According to the definition provided by the International River, “transboundary impact” refers to any impact, not necessarily of a global nature, within an area under the jurisdiction of one party caused by a proposed activity whose physical origin is wholly or partly within the jurisdiction of another party. Based on this definition, cooperation on transboundary surface waters and groundwaters is crucial for preventing conflicts, promoting sustainable development, enhancing climate change resilience, and fostering regional integration. This importance is recognized by including transboundary water cooperation in Sustainable Development Goal Target 6.5.

United Nations Global Water Conventions: A Framework for Transboundary Water Management

The United Nations has established two key conventions to address the management of shared water resources: the Watercourses Convention and the Water Convention. These conventions aim to foster international cooperation and ensure the sustainable use of transboundary water resources in light of growing global water scarcity. Both conventions’ key principles and mechanisms are grounded in equitable use, prevention of transboundary harm, and sustainable management of shared waters. They require member states to cooperate through specific agreements and joint bodies to address issues such as water quality, quantity, and ecosystem preservation (United Nations Economic and Social Council, August 2024).

Watercourse Convention

Adopted in New York in 1997 and coming into force in 2014, the Watercourses Convention, officially titled the Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, establishes a comprehensive legal framework for the equitable and reasonable use of international watercourses. It mandates member states to take necessary measures to prevent and control transboundary harm (United Nations, Global Water Conventions. 2021). Furthermore, the convention incorporates provisions for dispute resolution, including arbitration and fact-finding, which any disputing party may invoke.

Water Convention

The Water Convention, formally known as the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes, was adopted in Helsinki in 1992 and came into effect in 1996. Initially developed as a regional framework for Europe, it was made globally accessible in 2016, allowing all UN member states to participate (Geneva Environmental Network, Water Convention. 2024). This convention focuses on the sustainable management of shared surface and groundwater resources, fostering collaboration even in politically sensitive contexts (UNECE, Water for Peace. August 2024). Additionally, it underscores the necessity of legally binding agreements to enhance cooperation and ensure sustainability (IWRA Action Hub, “International Water Law,” n.d.). Since it entered into force, the Water Convention has facilitated over 100 agreements, demonstrating its role in enhancing peace and stability (UNECE, Water for Peace. August 2024).

The Global Water Crisis and the Role of Conventions

By 2050, an estimated 25% of the world’s population will live in countries facing chronic water shortages due to unsustainable practices and population growth (United Nations, Global Water Conventions. 2021). Addressing this crisis requires managing shared water resources equitably and sustainably. The UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development identifies the need for effective transboundary water management to achieve global water security and mitigate climate change impacts.

The Water Convention has been instrumental in fostering agreements across various regions. For example, it facilitated cooperation in the Drin River Basin, shared by Albania, North Macedonia, Greece, Kosovo, and Montenegro. Similarly, the Sava Agreement, involving Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia, exemplifies how transboundary water management can promote peace in post-conflict settings (UNECE, “Water for Peace,” 2024). As climate change exacerbates global water scarcity, the role of these conventions in fostering sustainability and conflict prevention becomes increasingly vital.

Despite progress, significant gaps remain in transboundary water management. Many agreements are non-operational due to the absence of critical riparian states or insufficient funding. For instance, in Africa, which has 64 transboundary rivers, 90 percent of freshwater lies in shared basins, yet many legal frameworks lack full implementation (UNECE, “Water for Peace. 2024).

Moreover, international water law faces challenges when certain nations, such as Syria, Turkey, and China, are not signatories to key agreements. Nevertheless, legal instruments like the Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques (ENMOD) and the Geneva Conventions provide additional tools to protect water resources and infrastructure (The Centre for Climate and Security, “Water Weaponization,” n.d.).

China’s Collaboration with Other Nations on Transboundary River Dam Construction Project

China shares 40 major transboundary watercourses with 16 countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Vietnam. Notably, more than two-thirds of China’s most critical transboundary rivers originate in China, which is upstream on most of its shared international watercourses.

China’s treaty practice includes interesting provisions related to the “ownership” of transboundary waters and the right to their use. For example, Article 2 of the 1962 China-Mongolia Boundary Treaty declares that “the water in the transboundary rivers is subject to common use.” China’s treaty practice also refers to the obligation not to cause harm; for example, the China-Mongolia Agreement and the China-Russia treaty use negotiations as the preferred approach for dispute settlement (Chen, Riew-Clarke, and Wouters, April 2013).

According to Chen, Riew-Clarke, and Wouters (2013), China’s approach to transboundary water management often diverges from international norms. Although China firmly supports the peaceful resolution of disputes, as outlined in the UN Charter (1945) and also a signatory of the Statute of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and is part of many bilateral and multilateral treaties that include provisions for settling disputes, the approach in China’s treaty concerning transboundary waters is linked to surface water but not confined groundwater, which is defined under international watercourses.

The author notes that China has border treaties with all neighboring countries except Bhutan and India, which are primarily bilateral but lack specific agreements on transboundary watercourses with India or Bangladesh. However, it signed a Memoranda of Understanding in 2008 with both countries regarding hydrological information for the Yarlung Zangbo/Brahmaputra River. China also adopts a similar approach to Vietnam and other Mekong River riparian states.

Why Large Dams Are Crucial for Modern Development

Definition, Lifespan, and Benefits of Large Dams

The United Nations University defines a large dam as a structure at least 15 meters high or capable of impounding over 3 million cubic meters of water. The average lifespan of these dams is approximately 50 years, with many built between 1930 and 1970 now nearing the end of their design life (United Nations University, January 2021). According to the International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD), there are 58,700 registered large dams worldwide, with China hosting 23,841—40% of the global total. Four Asian countries—China, India, Japan, and South Korea—account for 55% of the world’s large dams.

Image: Three Gorges Hydroelectric Gravity dam that spans the Yangtze River in central China. It is the world’s largest power station by installed capacity, 22,500 MW; Image credit: Wikipedia.org; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Gorges_Dam#/media/File:ThreeGorgesDam-China2009.jpg

Dams play a crucial role in energy production, flood management, water supply, agriculture, and providing drinking water, making them an indispensable component of future infrastructure. These benefits are especially vital for sustaining livelihoods and promoting development in many parts of the world (International Rivers, 2023). Often called the “temples of the modern economy,” dams contribute significantly to agriculture, irrigation, water storage, flood control, and electricity generation (Arora, Arushi. January 2024). In the 1900s, dams were seen as symbols of economic progress, with many developing nations building them to support their growth. About half of the world’s large dams were constructed to meet agricultural needs, supplying water to irrigate 30 to 40 percent of the 2.71 million square kilometers (1.05 million square miles) of irrigated farmland and grazing land worldwide (Kotze, Petro. April 21, 2022).

Dams have historically served as strategic military targets, as seen during World War II and the Korean War. Interestingly, a dam doesn’t need to be destroyed to act as a weapon. For example, the Itaipu Dam, situated on the border of Brazil and Paraguay, lies upstream of Argentina’s capital, Buenos Aires. If its sluice gates were fully opened simultaneously, it could unleash catastrophic flooding upon the city (Harford, Tim. BBC News, March 10, 2020).

Economic Progress vs. Environmental Consequences of Large-Scale Dams

While large dams support economic development, they also have significant environmental costs. They are responsible for soil erosion, species extinction, the spread of diseases, sedimentation, salinization, and waterlogging. Additionally, they disrupt the natural flow of rivers, fragment ecosystems, and destroy surrounding forests, which serve as vital carbon sinks. These disruptions impact migratory fish routes, preventing fish from spawning and creating cascading effects on predators like dolphins, which rely on these fish for food.

The financial and social costs of dams are substantial. Construction takes an average of 8.6 years, often exceeding time and budget estimates by over 44 percent (AIDA Americas, 2023). Many projects lead to forced displacement, loss of traditional livelihoods, and impoverishment of local communities. As dams age, safety concerns, maintenance costs, and the need to restore ecosystems have prompted a global trend toward dam decommissioning. In Europe, for instance, the Maigrauge Dam in Switzerland is expected to reach 200 years of age, while the U.S. has seen a rise in dam removals to address these challenges (International Rivers, 2023). Sustainable alternatives, such as renewable energy sources, offer more viable solutions for addressing energy and water needs.

Large Dams contribute to substantial ecological and climate challenges. For example, large dams have been linked to an 84 percent decline in average freshwater wildlife population sizes since 1970. Over a quarter of Earth’s land-to-ocean sediment flux is trapped behind dams, while decaying vegetation and nutrient sedimentation in reservoirs increase microbial activity, leading to significant greenhouse gas emissions. Large dams may even alter the Earth’s orbit due to massive shifts in water distribution across significant river systems (Arora, Arushi January 2024). Furthermore, dams disrupt the carbon cycle, impacting the planet’s climate (Kotze, April 21, 2022; Mongabay).

Large dams have profound environmental consequences. They trap sediment, disrupt aquatic habitats, and degrade water quality, leading to biodiversity loss and species extinction. Tropical dams release significant amounts of methane, a greenhouse gas 20–40 times more potent than carbon dioxide, due to the decay of organic matter in reservoirs (International Rivers, 2023). This makes hydropower projects less sustainable as climate-friendly energy sources. Furthermore, dams reduce the climate resilience of river communities by exacerbating the impacts of droughts and floods.

Despite their societal advantages, dams have significant adverse consequences on river ecosystems. By blocking rivers, they disrupt natural water cycles, slow water flow, and alter the timing of releases. These changes harm water quality, promote algal blooms, reduce oxygen levels, and adversely affect sensitive aquatic species. Furthermore, operating hydropower dams during peak demand periods exacerbates habitat loss by trapping sediment and burying riverbeds, critical for fish spawning (United Nations University, January 2021).

Case Studies and Regional Trends

While hydropower remains a significant renewable energy source, its prominence has declined in recent decades. The construction of large hydropower dams peaked in the 1960s, and in regions like Europe and the United States, more dams are now being removed than built. Environmental damage and economic inefficiency have driven this shift. For example, in the United States, hydropower contributes only about 6 percent of the nation’s electricity, highlighting the growing trend toward dismantling aging and unsustainable infrastructure (McGrath, November 2018). This balance between harnessing the benefits of dams and addressing their environmental and societal costs remains a pressing global challenge.

The cascading effects of large dams are evident in regions like the Mekong Delta in Vietnam. This delta, the world’s third-largest, supports nearly 20 million people and is vital for Southeast Asia’s food security. Despite the construction of several large dams on the Mekong River, additional hydropower projects are planned, raising concerns from Thailand’s National Human Rights Commission about environmental and social repercussions. The commission has urged the Thai Prime Minister to reconsider plans for four new dams near the Thai-Lao border (Sohsai, Rin. November 2024).

Large-scale hydropower dams on the mainstream of the Lancang/Mekong River; Image Credit: International Crisis Group; 07 October 2024; https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/cambodia-thailand-china/343-dammed-mekong-averting-environmental-catastrophe?utm_source=chatgpt.com

While large dam construction is declining in most parts of the world, Africa sees increased planned dam projects, becoming the region’s most significant water and energy investments (International Rivers, November 2023). For instance, the Democratic Republic of Congo has proposed the multi-billion-dollar Grand Inga Dam along the Congo River, which is anticipated to generate an impressive 40,000 MW of electricity—sufficient to power New York City during peak summer months (BBC, January 2025). There are 300 million people currently without electricity on the African continent (Miriri, Duncan. Reuters, January 27, 2025).

Global Risks and Catastrophic Failures of Large Dams

Dams offer the added benefit of incorporating hydroelectric power stations, providing a renewable energy source that surpasses nuclear, solar, wind, and tidal in scale. Large reservoirs, when full, can weigh over 100,000 million tones, potentially triggering earthquakes, while smaller ones may still cause deadly landslides (Harford, Tim. BBC News, March 10, 2020). As large dams age, they exhibit structural decay, rising maintenance costs, and sediment buildup, leading to predictions of increased decommissioning in regions such as the U.S. and Europe (Yale Environment 360, 2021). Many large dams worldwide are aging, becoming unsafe, and losing their original functionality. Sediment buildup, increasing maintenance costs, and structural safety risks make these dams less viable. Policymakers must address these growing concerns while considering the environmental benefits of decommissioning outdated infrastructure to restore natural river systems (United Nations University, 2021).

Aging dams pose significant risks, evidenced by catastrophic failures like the Toddbrook Dam collapse in Britain in 2019 and the Oroville Dam spillway failure in California in 2017 (Horgan, Rob. April 2020). The Banqiao Dam disaster in China in 1975, caused by extreme rainfall, resulted in over 26,000 immediate fatalities and up to 170,000 additional deaths from famine and epidemics, marking it as the deadliest structural failure in history (Yale Environment 360, 2021). In a seismic zone, the Mullaperiyar Dam in India severely threatens over 3 million people downstream, particularly in a significant earthquake (Pearce, Fred. February 2021). These examples highlight the growing dangers of aging infrastructure and the compounding effects of climate-induced stresses.

Water as a Weapon: Historical and Modern Dynamics

The Role of Water in Conflict and Cooperation: Understanding Water Weaponization

Water has historically been both a source of conflict and a tool of cooperation among states. The phenomenon of water weaponization, a deliberate act to use water or water-related infrastructure as a strategic or tactical tool in conflicts, is well-documented across centuries. Marcus King of the Centre for Climate and Security developed a six-category matrix to classify water weaponization: Strategic, targeting large populations or infrastructure; Tactical, focusing on military targets; Coercive, to achieve compliance; Unintentional, causing collateral damage; Psychological Terror, creating fear among civilians; and Extortion/Incentivization, exploiting water access for control or gain (Centre for Climate and Security). For instance, strategically targeting a dam can devastate downstream settlements and destroy ecosystems unintentionally, as seen in water-related incidents in Africa and the Middle East. These frameworks highlight the profound instability water weaponization can drive, especially in regions already stressed by political and environmental pressures.

Modern Instances of Water Weaponization: Ukraine, Yemen, and Libya

The modern era has witnessed a rise in the weaponization of water, with 28 incidents recorded since 2020 compared to 32 in the prior decade (New Security Beat, March 2024). Notable examples include the destruction of the Nova Kakhovka Dam during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, displacing 3,600 people and disrupting water supplies for one million, and Yemen’s civil war, where water access was weaponized by Houthi forces and the Yemeni government, worsening the humanitarian crisis. Similarly, in Libya, the 2023 collapse of dams in Derna caused catastrophic flooding, claiming over 4,000 lives and displacing 42,000. These incidents highlight the devastating impacts of targeting water infrastructure, particularly in water-scarce and climate-vulnerable regions.

The Crisis of Free-Flowing Rivers: Large Dams, Ecosystems, and Climate Challenges

Free-flowing rivers are increasingly threatened, with dams being one of the most significant challenges. Poorly placed dams can alter water flows, block fish migration, devastate endangered species habitats, and trap nutrient-rich sediment essential for downstream deltas (WWF, Summer 2021). Since 1950, large dams have increased tenfold, with over 58,000 existing today. A 2019 WWF study revealed that nearly two-thirds of the world’s long rivers are now impeded.

Rivers, such as the Nile in Egypt and the Yangtze in China, have historically supported civilizations. Beyond their cultural and historical importance, free-flowing rivers are vital ecosystems, home to over 100,000 freshwater species, and provide essential resources like food and clean water. However, only one-third of the world’s longest rivers remain free-flowing, and the climate crisis exacerbates their decline. Aging dams further compound the risks as their structures grow weaker under the pressures of climate change and extreme river flows (Pearce, Fred. February 2021).

International River Agreement Practice

The 1997 United Nations Watercourses Convention (UNWC)) establishes key principles for the equitable and sustainable management of shared water resources. It emphasizes the need for states to use transboundary watercourses equitably and reasonably without causing significant harm to other riparian countries. The Convention highlights that Cooperation, prior notification, and consultation are central to fostering peaceful relationships and addressing potential conflicts. It also stresses the importance of protecting the environment of shared watercourses to ensure their long-term sustainability, promoting regional cooperation and the responsible use of water resources.

The Nile Basin Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA) is a significant international agreement signed by Ethiopia, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Kenya, and Burundi (Nile Basin Initiative. Cooperative Framework Agreement). This agreement outlines the basic principles for the protection, sharing, and management of the Nile Basin, and it was largely modeled on the UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses.

Another example is the longstanding cooperation between the United States and Mexico, which have shared the Rio Grande (Río Bravo) river basin for over 170 years. This river links the two nations through more than 2,000 kilometers of international border and shared natural resources, wildlife habitats, socio-economic systems, and deep cultural and historical ties (Salman, Dr. M.A. July 2024). Flowing through a national park in Texas, the Rio Grande is managed under a complex framework of border treaties, national and state laws, and institutional arrangements. The author highlights the 1944 Treaty on the Utilization of Waters of the Colorado, Tijuana, and Rio Grande Rivers, widely praised for fostering innovative and cooperative governance of these vital waterways.

Conclusion

The Brahmaputra River Dam project, proposed by China, is a highly significant and controversial initiative due to its vast scale and potential impact on the surrounding regions. The dam, to be constructed on the Yarlung Tsangpo River in Tibet, is expected to be the largest of its kind, capable of generating substantial hydropower with the potential to supply electricity to millions of homes. While the project promises economic benefits for China, such as energy generation and water management, it has raised significant concerns for downstream countries, particularly India and Bangladesh.

India’s primary concerns center around the potential reduction in water flow, which could harm agriculture, drinking water supplies, and livelihoods in northeastern states like Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. The impact of seasonal flooding and droughts, already prevalent in the region, could worsen with changes in the river’s water flow patterns. Additionally, India is apprehensive about China’s increasing control over transboundary water resources, fearing that this could be used as a tool for geopolitical leverage, particularly in times of conflict.

China’s dam construction also poses serious environmental and climate-related risks, including ecosystem disruption, biodiversity loss, and alteration of sedimentation patterns, which could undermine soil fertility in agricultural regions. The region’s vulnerability to climate change, such as glacial melting and extreme weather events, further amplifies these concerns. Moreover, the river flows through the disputed territory of Arunachal Pradesh, a point of tension between China and India, making the project an environmental and economic issue and a geopolitical one.

The United States also expresses concerns over China’s growing influence in the Indo-Pacific region, particularly its control over transboundary water resources like the Brahmaputra. The project could further exacerbate regional geopolitical tensions, potentially disrupting established power dynamics, increasing water competition, and challenging U.S. interests in maintaining stability and cooperation within the Indo-Pacific.

Overall, the Brahmaputra Dam project has sparked intense debate over the balance between economic development and environmental protection. India and Bangladesh are concerned about its far-reaching consequences on water security, regional stability, and climate change.

List of References:

- AIDA Americas. “Dam No More: The Truth About Large Dams, 2023” https://aida-americas.org/en/dam-no-more-truth-about-large-dams

- Anand, Brig Vinod. “Hydropower Projects Race to Tap the Potential of Brahmaputra River.” Vivekananda International Foundation, February 7, 2013. https://www.vifindia.org/article/2013/february/07/hydro-power-projects-race-to-tap-the-potential-of-brahmaputra-river.

- Arora, Arushi. “Dams: Economic Assets or Ecological Liabilities?” January 18, 2024. https://earth.org/dams-economic-assets-or-ecological-liabilities/.

- BBC. “Grand Inga Dam: The World’s Largest Hydropower Project Proposed in the Democratic Republic of Congo.” BBC News, January 26, 2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c62jmq0z89jo.

- Bhattacharya, Rajiv. “India’s Response to World’s Largest Dam in China Faces Local Opposition.” The Diplomat, January 8, 2025. https://thediplomat.com/2025/01/indias-response-to-worlds-largest-dam-in-china-faces-local-opposition/.

- Centre for Climate and Security. “Water Weaponization: International Legal Instruments.” https://climateandsecurity.org/2023/06/water-weaponization-its-forms-its-use-in-the-russia-ukraine-war-and-what-to-do-about-it/

- Centre for Climate and Security. “Water Weaponization Matrix.”

- Chen, Huiping, Alistair Riew-Clarke, and Patricia Wouters. “Exploring China’s Transboundary Water Treaty Practice through the Prism of the UN Watercourses Convention.” Water International 38, no. 2 (2013): 217-230. Published online April 9, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2013.785799.

- CNA Analysis and Solutions. “Water Resources Competition in the Brahmaputra River Basin: China, India, and Bangladesh.” May 2016. https://www.cna.org/archive/CNA_Files/pdf/cna-brahmaputra-study-2016.pdf.

- Geneva Environmental Network. “Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes.” 2024. https://www.genevaenvironmentnetwork.org/environment-geneva/organizations/convention-on-the-protection-and-use-of-transboundary-watercourses-and-international-lakes/.

- Harford, Tim. “The Spectacular Failures and Successes of Massive Dams.” BBC News, March 10, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-51459930.

- Horgan, Rob. “Toddbrook Dam Collapse: Closing the Gap Between Compliance and Safety Must Be Priority.” New Civil Engineer, April 2, 2020. https://www.newcivilengineer.com/latest/toddbrook-dam-collapse-closing-gap-between-compliance-and-safety-must-be-priority-02-04-2020/.

- International Rivers. “Hydropower Industry.” November 21, 2023. https://www.internationalrivers.org/issues/corporate-accountability/hydropower-industry/.

- International Rivers. “People, River, Life: Hydropower Industry.” https://www.internationalrivers.org/issues/corporate-accountability/hydropower-industry/.

- iLearn CANA. “Indo-Pacific Region”, October 26, 2022. https://ilearncana.com/details/Indo-Pacific-region/3716.

- IWRA Action Hub. “International Water Law: Tool A2.02.” https://iwrmactionhub.org/learn/iwrm-tools/international-water-law.

- Kotze, Petro. “The World’s Dams: Doing Major Harm but a Manageable Problem?” Mongabay, April 21, 2022. https://news.mongabay.com/2022/04/the-worlds-dams-doing-major-harm-but-a-manageable-problem/.

- Manhas, Neeraj Singh, and Rahul M. Lad. “China’s Weaponization of Water in Tibet: A Lesson for the Lower Riparian States.” Published March 12, 2024. https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/3703876/chinas-weaponization-of-water-in-tibet-a-lesson-for-the-lower-riparian-states/

- McGrath, Matt. “Large Hydropower Dams ‘Not Sustainable’ in the Developing World.” BBC, November 5, 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-46098118.

- Miriri, Duncan. “African Nations Seek to Connect 300 Million People to Power by 2030.” Reuters, January 27, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/african-nations-seek-connect-300-mln-people-power-by-2030-2025-01-27/

- NASA Earth Observatory. “The Braided Brahmaputra.” November 9, 2020. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/147591/the-braided-brahmaputra.

- Nile Basin Initiative. “Cooperative Framework Agreement.” https://nilebasin.org/about-us/cooperative-framework-agreemen.

- New Security Beat. “The Global Challenge of Water’s Weaponization in War: Lessons from Yemen, Ukraine, and Libya.” March 22, 2024. https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2024/03/the-global-challenge-of-waters-weaponization-in-war-lessons-from-yemen-ukraine-and-libya/

- Pasricha, Anjana. “World’s Largest Dam to Be Built by China Raises Concerns in India, Bangladesh.” Voice of America, January 9, 2025. https://www.voanews.com/a/world-s-largest-dam-to-be-built-by-china-raises-concerns-in-india-bangladesh/7931076.html.

- Pearce, Fred. “Water Warning: The Looming Threat of the World’s Aging Dams.” Yale Environment 360, Yale School of the Environment, February 3, 2021. https://e360.yale.edu/features/water-warning-the-looming-threat-of-the-worlds-aging-dams.

- Samaranayake, Nilanthi, Satu Limaye, and Joel Wuthnow. “Water Resources Competition in the Brahmaputra River Basin: China, India, and Bangladesh.” May 2016. https://www.cna.org/archive/CNA_Files/pdf/cna-brahmaputra-study-2016.pdf.

- Salman, Dr. M.A. “International Water Law Project Blog.” July 15, 2024. https://www.internationalwaterlaw.org/blog/.

- Siow, Maria. “China’s Himalayan Mega Dam Deepens India’s Water Worries.” South China Morning Post, January 18, 2025. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/economics/article/3295257/chinas-himalayan-mega-dam-deepens-indias-water-worries

- Sohsai, Rin. “Thailand’s National Human Rights Commission Raises Serious Concerns about Impacts of Mekong River Dams.” International Rivers, November 8, 2024. https://www.internationalrivers.org/.

- The Centre for Climate and Security. “Water Weaponization: International Legal Instruments.”

- The Government of Assam. “Water Resources, River System of Assam.” https://waterresources.assam.gov.in/portlet-innerpage/brahmaputra-river-system#:~:text=The%20Brahmaputra%20Valley%20has%20an,respect%20to%20its%20average%20discharge.

- Times of India, December 26, 2024, China Plans World’s Largest Dam on Brahmaputra: How Will It Impact India.” https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/china-plans-worlds-largest-dam-on-brahmaputra-how-will-it-impact-india/articleshow/116682819.cms.

- United Nations Economic and Social Council. “Economic and Social Council Distr. ECE/MP.WAT/2024/2, August 14, 2024.” https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2024-09/ECE_MP.WAT_2024_2_draft_POW_2025-2027_ENG.pdf.

- United Nations University. “Ageing Dams Pose Growing Threat.” January 22, 2021. https://unu.edu/press-release/ageing-dams-pose-growing-threat.

- United Nations. “Global Water Conventions: Fostering Sustainable Development and Peace.” Dec 01, 2020. https://www.unwater.org/sites/default/files/app/uploads/2021/01/UN-Water_Policy_Brief_United_Nations_Global_Water_Conventions.pdf.

- UN Water. 2024. Progress on Transboundary Water Cooperation – 2024 Update. United Nations. October 1, 2024. https://www.unwater.org/publications/progress-transboundary-water-cooperation-2024-update.

- UN Water. 2024. SDG 6 Indicator Report 6.5.2: Progress on Transboundary Water Cooperation – 2024. September 2024. https://www.unwater.org/sites/default/files/2024-09/SDG6_Indicator_Report_652_Progress-on-Transboundary-Water-Cooperation_2024_EN.pdf.

- WWF. “A Dam Predicament.” Summer 2021. https://actvironment.com/wp-admin/post.php?post=1643&action=edit.

- Yale Environment 360. “Water Warning: The Looming Threat of the World’s Aging Dams.” Yale School of the Environment, February 3, 2021. https://e360.yale.edu/features/water-warning-the-looming-threat-of-the-worlds-aging-dams

- Zhang, Anni. “China’s Himalayan Mega Dam Deepens India’s Water Worries.” South China Morning Post, January 18, 2025. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/economics/article/3295257/chinas-himalayan-mega-dam-deepens-indias-water-worries